By now, the ruling party’s victory celebrations have become a familiar affair for the country. The dhol beats, the firecrackers at the BJP headquarters in Delhi—and this time in Maharashtra too—and, of course, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s message of gratitude to his untiring party apparatchiks and workers. After the huge disappointment in the general election this June, where the party fell agonisingly short of a simple majority mark on its own, normal service has been restored.

The turnaround victory in Maharashtra—a major factor in that underwhelming Lok Sabha effort—has rubbished any doubts on the core competency of the BJP’s election machinery with Modi as its totem. At the heart of the Mahayuti sweep was the BJP’s solo tally of 132 seats out of the 148 it contested, a near-90 per cent strike rate and a far cry from the nine LS seats it won out of the 28 it contested some five months back. The Jharkhand results may have led to some hand-wringing, but the national impact of winning Maharashtra, with its outsize influence on India’s economy, puts everything else in the shade. Indeed, for BJP enthusiasts, it has been months of cheer, inaugurated by a miraculous win in Haryana against a decade of anti-incumbency, and a creditable performance in the first assembly poll in Jammu and Kashmir since the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019. All of this has ensured that Modi 3.0 can continue to peddle the soft Hindutva line while having enough headroom to dodge any googly by the Congress-led Opposition in Parliament.

ALL IS FORGIVEN

The turnaround, though, would not have been possible without the BJP leaders first making peace with their counterparts in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The ideological patron had been upset for some time at the goings-on in Modi 2.0, the fact that the BJP leaders didn’t consult them on key appointments, or the way the party had forsaken ideology to engineer defections and topple Opposition governments. It all came to a head after BJP chief J.P. Nadda’s comment during the LS poll campaign that the party was “saksham (capable)” in handling its own affairs, that it had outgrown the RSS.

Many analysts attributed the statement to the Sangh’s visible absence from the BJP campaign at crucial junctures. The disappointing results of the general election gave the opportunity to the RSS leadership to hit back, with even sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat allowing himself some scarcely veiled censuring of PM Modi. It took a series of parleys between the two sides to break the ice, but not before the BJP made major concessions. This saw the return of vintage RSS man Ram Madhav to the BJP in August to deal with the J&K polls and the deployment of Sangh sah-sarkaryavahs Arun Kumar (in Haryana), Atul Limaye (Maharashtra) and Alok Kumar (Jharkhand) for election coordination. Their job apparently was to “reactivate the core voters and re-enthuse the sympathisers”.

Sangh sources say workers from 65 affiliate organisations were on the ground in Maharashtra and some 150,000 small to large meetings were held. Even the poll assignments to Union minister and Nagpur native Nitin Gadkari had the Sangh’s hand written all over it. The poll results have since shown how crucial the larger Sangh Parivar is to the success of the party.

THE NEW TEMPLATE

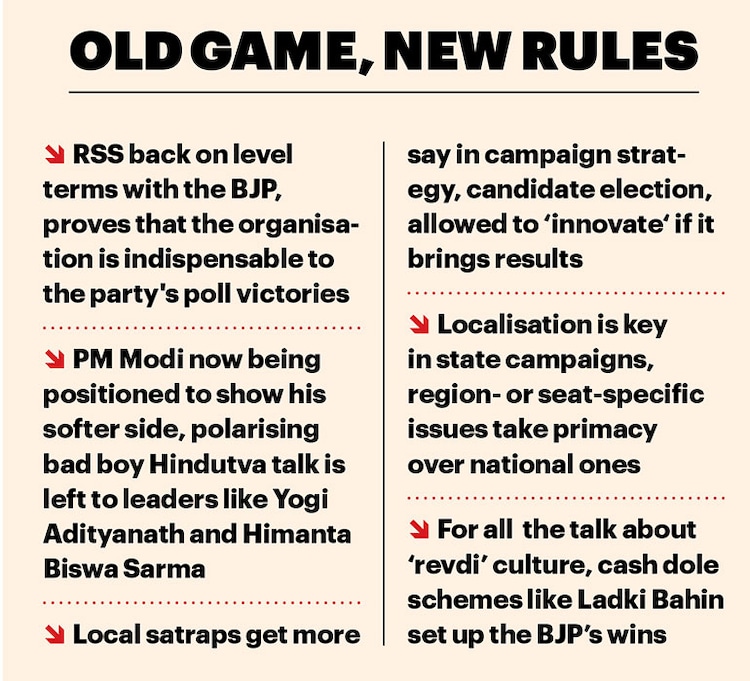

Unlike in the past, when PM Modi used to do much of the heavy lifting in poll campaigns, the party has been more strategic in how much he is exposed on the frontline. In his third term, the prime minister held just five rallies in Haryana, 10 in Maharashtra and four in Jharkhand. The pattern has been—make the contest about local issues, not about Modi versus the Others. This has allowed the BJP to set the agenda and also make best use of the massive RSS organisation.

The PM is also adopting a softer line. So, while he mouths the milder rhetoric, like the slogan “Ek hai to safe hai (United, we are safe)”, it is left to the likes of Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath and his Assam counterpart Himanta Biswa Sarma to push the harder Hindutva line. Accordingly, Yogi campaigned with the slogan ‘Batenge to katenge (Divided, we’ll be felled)’ and ‘vote jihad’ in Maharashtra, and Sarma sounded a ‘Muslim infiltration’ alarm in Jharkhand, alleging that the tribal Santhal Parganas area was turning into a “mini Bangladesh”.

The PM is also becoming measured in his reaction to Opposition campaigns. For instance, his choice not to retaliate to their ongoing ‘Samvidhan bachao (save the Constitution)’ protest has ensured that the issue is not catching fire a second time. And while he continues to take on national figures like the Gandhi family, PM Modi avoids attacking local grandees, such as Sharad Pawar and Uddhav Thackeray in Maharashtra. BJP insiders say it’s part of a deliberate strategy, as in Maharashtra, and allowed the party to control the narrative and make the contests very local rather than becoming a Modi versus Pawar or a Modi versus Uddhav battle.

In a related intervention by the Sangh, the BJP is also allowing local satraps to have more say in electoral campaigns. Gadkari stationed himself in Maharashtra’s Vidarbha region, holding 73 rallies. The RSS also ensured he had a say in candidate selection and campaign design. The result: the BJP-led Mahayuti won 40 of the 62 assembly seats in the region. In the LS polls, farmers’ distress and the Maratha agitation had helped the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) alliance win seven of the 10 constituencies here.

Similarly, Mahayuti ally Ajit Pawar’s Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) was allowed to defy the Hindutva line in western Maharashtra. The BJP think-tanks realised their hardline slogans were not working here; an added complication was the local cadre unhappy at allying with Ajit. That had reflected in the Lok Sabha polls, when the NDA was wiped out in the region. The Sangh’s job was to ensure the BJP and Shinde Sena votes got transferred to Ajit’s candidates, despite his defiant posturing. This is a playbook used in Haryana too, when satraps like Union ministers Rao Inderjit Singh and Krishanpal Gurjar were allowed to ‘innovate’ in the campaign.

SAFFRON TWIST TO REVDI

For all the distaste PM Modi and others have expressed for the ‘revdi (dole)’ culture, few in the BJP dispute its importance in ‘election messaging’. The RSS cadre ensured that they relayed the messaging effectively to the grassroots. The Sangh apparatus started constituency-wise deployment from August onwards and also put a feedback mechanism in place. This helped the party identify and address key issues. Party insiders say it also provided RSS leadership leverage in bringing BJP leaders to the discussion table in poll-bound states.

The strategy sweetener in all this was the cash doles and welfare schemes. Both Haryana and Maharashtra dished out versions of the Ladli Behna, the cash dole scheme for women that had been a massive success in Madhya Pradesh. In Maharashtra, it became the Ladki Bahin scheme which transferred Rs 1,500 every month to 23 million women beneficiaries with a promise of a top-up of Rs 600 and expanding the number of beneficiaries by 2 million.

The election in Maharashtra also marks a return to the party’s polarising agenda, though couched in the euphemistic slogan of ‘Ek hai toh safe hai’. PM Modi reiterated it in his victory speech after the Maharashtra election, saying, “The voters of Maharashtra have stopped the conspiracy hatched by the Congress and their friends. Maharashtra has given a verdict—‘Ek hai toh safe hai’ is India’s mantra.” The BJP-RSS had realised the slogan’s resonance during the Haryana polls, where the war cry had enthused the party cadre. Critics, of course, charge the BJP of returning to its old game of pitting Hindu voters against Muslim ones. They argue that it is the antithesis of the ‘Sabka saath, sabka vikas’ plank on which Modi rode to power. BJP insiders counter that the pitch is an attempt to make party sympathisers aware of “global threats” and “reverse polarisation”, especially with minority votes coalescing in favour of the INDIA bloc over issues like Ayodhya, the Waqf (Amendment) Bill 2024, Uniform Civil Code and anti-conversion laws. The ‘unity’ call is also seen as a BJP-RSS strategy to divert attention from the Opposition’s push for a caste census. The view in the Sangh Parivar has always been that the caste census, by design, was aimed at fragmenting Hindu society.

FRAYING AT THE SEAMS

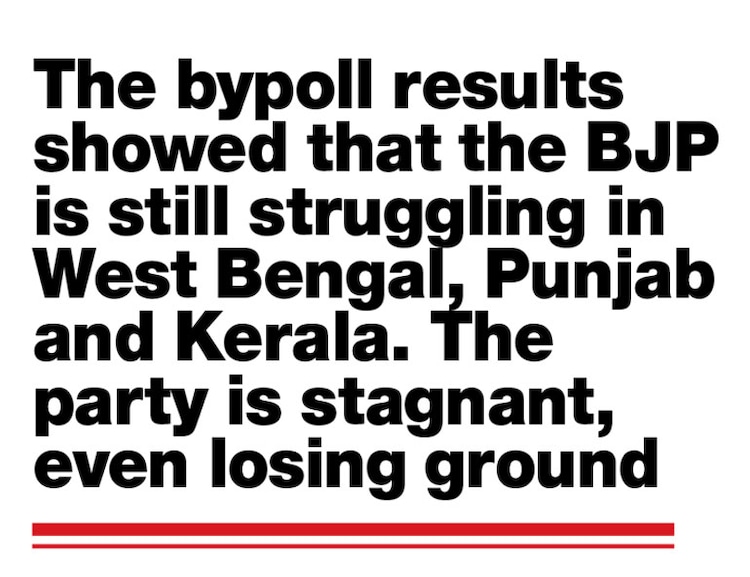

Even as the Maharashtra victory overshadowed all else, Jharkhand and the bypoll results show that there is work still to be done. States like West Bengal, Punjab and Kerala continue to elude its grasp. The party is stagnant, even losing ground, in these states that together account for 75 Lok Sabha seats. Add Tamil Nadu, with its 39 LS seats, as an extension of that unbreached frontier. The BJP holds only 12 of these 114 seats—11 in Bengal, one in Kerala. For its Mission 2029 plan to succeed, repairs and recalibrations are crucial.

In the bypolls, the BJP lost in all the seats in Bengal (6), Punjab (4) and Kerala (2). The most painful of these losses will be in Madarihat in north Bengal and Palakkad in Kerala. In Madarihat, a former BJP bastion, the party lost in the absence of a strong narrative and organisational impetus; the fight in Palakkad was marred by massive factionalism. The next two months should see an overhaul of the party organisation in all four states. The knives are already out in Kerala for state president K. Surendran; in Punjab, Sunil Jakhar faces the same fate. The party has no option but to hit the refresh button in these state units, for it’s already late. Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Kerala will go to the polls in 2026. Punjab’s reckoning will happen in 2027.

In Bengal, the BJP had hoped to gain, riding on the protests in the RG Kar Hospital rape-murder case, but it was not to be. The party has an aggressive leader in Suvendu Adhikari, but BJP sources say the lack of a Sangh background is a handicap for him in the organisation. In Kerala, the BJP had tasted LS success for the first time with actor-turned-neta Suresh Gopi winning from Thrissur. So there were high hopes for the neighbouring Palakkad assembly seat, where the BJP has always had a strong showing. But here again, infighting seems to have ruined whatever chances they had. Similarly, in Punjab, the BJP had hoped the anti-incumbency vote against CM Bhagwant Mann and the absence of the Akali Dal would help the party gain some ground in the rural belt. But the BJP candidates lost their deposit in three of the four seats. This, despite fielding former ministers Manpreet Badal, Ravikiran Kahlon and Sohan Singh Thandal from their respective strongholds.

But barring these holdouts, the BJP can now truly claim to be the ‘superparty’ of the country. The back-to-back assembly poll victories have reinforced the belief that the leadership has learned from its mistakes and is nimble enough to make corrections. Next up is a prize ticket, the Delhi assembly election in February, and the RSS-BJP combine will fancy their chances against wounded Aam Aadmi Party frontman Arvind Kejriwal, who’ll be looking to make it three terms in a row. The saffron combine has been looking to breach Delhi’s gates for a long time. If it happens, one can be sure the celebrations will take a long time to wind down.

Author: VS NEWS DESK

pradeep blr